PATRICK BAILEY of Aghowle

May we remember Lance Corporal Patrick Bailey of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, who died on May 22nd 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium.

Born in Aghowle on January 28th 1896 to Christopher Bailey and Margaret Neill, Patrick Bailey would enlist in Carlow Town at the outbreak of war. The 2nd Battalion, having suffered horrific casualties during the Battles of the Marne and Messine, would replenish their ranks with fresh faces, including Bailey. He was clearly an aspiring and assertive soldier, having risen to the junior NCO rank of Lance-Corporal within a year of enlisting.

The Battalion entered the Ypres theatre in early May 1915 and quickly adapted to the brutal environment within the St. Julien sector within the British 4th Division. It seems Bailey died on May 22nd, a day before his fellow comrades would suffer horrific gas and shellfire attacks from the Germans during the Battle of Bellewaarde. The War Diary for his unit simply states that they suffered immense night time shelling from the Germans on the nights of May 21st and May 22nd, having sustained no damage during daylight hours. Bailey may have died as a result of these night bombardments. Having entered the trenches with 666 men, the remnants of the Battalion made it back behind the lines with only twenty soldiers in full health.

Bailey’s remains were never recovered. The cause of death is unknown; whether he succumbed to shellfire or blasted by machine-guns, we do not know. All that remains to remember Patrick Bailey’s existence are his state birth registration, enlistment papers, the photograph held by relations, his eerie soldier’s will and the memorial at Menin Gate at Ypres to remember all those who have no known grave. Let’s remember the life of the 19 years old, Patrick Bailey of Aghowle.

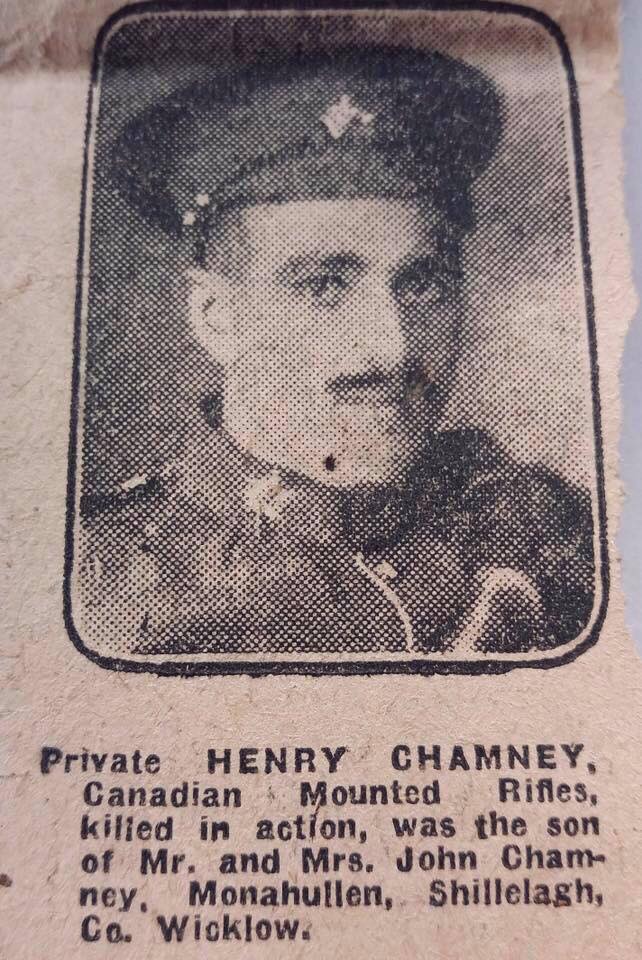

HENRY CHAMNEY of Munahullen

Henry Chamney was born on February 25th 1891 in the townland of Munahullen, near the boundaries of Boley, Raheenakit and Crone to John Chamney of Munahullen and Mary Stacey of Lumcloon. He was present at the farming homestead for both the 1901 and 1911 Census’ and very little other records survive about Henry’s early life.

Between 1911 and the outbreak of war in 1914, it seems that Henry had emigrated to Ontario, Canada, where many families from the Coolkenno area had moved to only a generation before. Having sailed aboard The Adriatic, he entered Ellis Island in New York in 1912 and obviously moved north to Canada. Clearly moved by the progress of the war, Chamney enlisted into the Canadian Mounted Rifles at Ingersoll, Ontario, on January 21st 1915.

The 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles were soon sent to the Western Front and would enter the Ypres theatre in Belgium. The Front was still at a deadlock and Chamney must have been astounded at the bleak, battered and devastated landscape; the smell of death and the continuous pounding of shells. Everywhere was a ruin. There was no sign of natural life bar of those who were there to fight.

Chamney’s regiment, the 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles, attached to the Canadian Corps would take up positions in the trenches, just several miles from the ruined medieval town of Ypres. Suddenly, on June 2nd 1916, in order to divert British resources from the build-up being observed on the Somme, the XIII (Royal Württemberg) Corps and the 117th Infantry Division attacked an arc of high ground positions, defended by the Canadian Corps. The German forces would capture the heights at Mount Sorrel and Tor Top, before entrenching on the far slope of the ridge. Following a number of attacks and counterattacks, two divisions of the Canadian Corps, supported by the 20th Light Division and Second Army siege and howitzer battery groups, recaptured the majority of their former positions.

Located in the Ypres Salient, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) east of Ypres, Belgium and 1,100 m (1,200 yd) from Hill 60, the Battle of Mount Sorrel took place along a ridge between Hooge and Zwarteleen. The crest of Mount Sorrel, nearby Tor Top (Hill 62) and Hill 61 rose approximately 30 metres (98 ft) higher than the shallow ground at Zillebeke, affording the occupying force excellent observation over the salient, the town of Ypres and approach routes. The peaks were the only portion of the crest of the Ypres ridge which remained in Allied hands. We can only imagine how Henry Chamney and his pals felt as they entered their baptism of fire.

It was noted by the commanders that the Canadian troops were overlooked by German positions and under constant danger of enemy fire. They assigned 3rd Canadian Division commander, Major-General Malcolm Mercer to draw up a plan to overrun the more dangerous German positions in a local attack. Chamney would be part of this attack.

As Chamney and his Canadian comrades began preparations for an assault, the Germans were in the process of executing an assault plan of their own. The XIII (Royal Württemberg) Corps spent six weeks planning and carefully preparing their attack on the Mount Sorrel, Tor Top (Hill 62) and Hill 61 peaks. Their objective was to take control of the observation positions east of Ypres and keep as many British units as possible pinned down in the area, to avoid them transferring to the Somme front and assisting with the observed build-up in that area. The Germans constructed practice trenches resembling the Canadian positions near Tor Top to rehearse the assault, well behind their own lines.

Prior to the war, most of the terrain around Mount Sorrel was heavily wooded with lush forests such as Maple Copse, Armagh Wood and Sanctuary Wood, all jagged and twisted stumps, erupting from the shell-pocked ground by the time Private Henry Chamney arrived. In mid-May, aerial reconnaissance near Mont Sorrel indicated that German forces were preparing an attack. Royal Flying Corps (RFC) observers had noted the existence of works curiously resembling the Canadian positions, well behind the German lines. The Germans were also observed digging new sap trenches which implied that an assault was intended. The Canadian Corps had just begun developing plans to overrun the more dangerous German positions, when the Germans executed an assault of their own.

On the morning of 2 June, the German XIII Corps began a massive heavy artillery bombardment against the Canadian positions. Nine-tenths of the Canadian forward reconnaissance battalion became casualties during the bombardment. The 3rd Canadian Division commander Major-General Malcolm Mercer and 8th Canadian Brigade commander Brigadier-General Arthur Victor Seymour Williams had been conducting an inspection of the front line, when the shelling began. Mercer was wounded three times and died early on 3 June; Williams was wounded in the face and head and taken prisoner. It must’ve been a tremendous barrage that blasted around the Canadian positions, keeping young Chamney low within his trench.

At 1:00pm, German pioneers detonated four large mines near the Canadian forward trenches, before the Germans attacked with six battalions, five more battalions in support and an additional six in reserve. When the German forces attacked, mainly against positions held by the 8th Canadian Brigade, resistance at the front lines was "minimal". For several critical hours both the 3rd Canadian Division, to which Chamney belonged, and the 8th Canadian Brigade were leaderless and their level of defence suffered accordingly. Brigadier-General Edward Spencer Hoare Nairne of the Lahore Divisional Artillery, eventually assumed temporary command of the 3rd Canadian Division. German forces were still able to capture Mont Sorrel and Hill 61. After advancing up to 1,100 metres (1,200 yd), the XIII Corps troops dug in. Although the road to Ypres was open and undefended, no German officer took the initiative to exceed instructions and capitalize on the success experienced by the German forces.

It is not known exactly from the records the exact moment of the opening hours of the Battle of Mount Sorrel in which Private Henry Chamney died. It is stated on his army death record that he died from “the concussion of a shell in Maple Copse, in the afternoon of June 2nd 1916”; his first and only day of participating in a battle. It appears that a German shell struck quite close to Chamney’s position, and judging that his remains were never located for later burial, it would seem that his mortal remains had been sadly obliterated. His name is recorded alongside many thousands of other missing soldiers, at Menin Gate at Ypres, Belgium.

Now you know of the story of another Coolkennovian who fell in the Great War of 1914-18. It was to be Private Henry Chamney’s first and only participation in battle.

James McDonald of Tullowclay

May we remember young James McDonald of Tullowclay. He was born on June 14th 1897 to Edward McDonald of Tullowclay and Nanny Halligan, originally of Killinure. His parents had married at the Oratory in the old Parochial House of Killinure on February 17th 1890 and bore a daughter, Elizabeth McDonald, before James came along.

The 1901 Census shows a large extended family residing in the small cottage that once stood along what is now Tompkins’ Lane. By the time of the 1911 Census, James McDonald is recorded as a fourteen year old Agricultural Labourer, a common, yet tough employment for most of the young adolescents of the Coolkenno Area at that time.

At the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, young James was clearly motivated to join the military and escape the monotony of working on a farm. He bid farewell to his parents and young sisters and enlisted into the Royal Field Artillery at Naas, Co. Kildare. On April 19th 1916, whilst apart of the No.3 section of the 30th Division of the Ammunition Column, Gunner James McDonald was killed. The “Nationalist & Leinster Times” newspaper recorded his death in detail. “Mrs. McDonald, Tullowclay, has received the following letter from:

“Somewhere in France, April 22nd 1916; - Dear Mrs. McDonald and family. It is with deepest regret I write these few words to inform you of the death of your son. He was only amongst us a few days, but during that time, we found him a cheerful comrade. He was buried in the village graveyard with full military honours, the local Catholic padre officiating. It was a most touching incident, and a lot of the villagers attended and showed deep sympathy. They presented a beautiful wreath, as also the officers and non-coms, and men of the No. 3 Section to which he had been attached when the sad incident took place. I am enclosing your son’s cap badge, which you will no doubt like to keep as a momento of him who came to do his duty to his King and Country, and who made the supreme sacrifice. I will now close, assuring you of the deepest sympathy on behalf of his comrades in your sad bereavement - Corporal J. Kenyon, No. 3 Section, 30 D, R.C. , British Expeditionary Force.”

The cause of his death is not actually recorded. Gunner James McDonald is interred, not within a Military Cemetery, but within a communal graveyard at Argoeuves, near Amiens, France. James McDonald is the only Coolkennovian, who served in the Great War, to have a known grave.

Peter St. LEDGER of Aghowle

As a child I always heard of a St. Ledger man, or locally pronounced as Sallinger, having died aboard the Titanic. I checked the records of those who embarked upon that ship and naturally there was no sign of him. A frustrating search as I knew little about the St. Ledger’s other than the last of name died in 1974; Paddy St. Ledger of Aghowle.Paddy’s younger brother, Peter, unexpectedly came to light when I purchased the recent publication, “Wicklow’s War Dead 1914-18.” I was dumbfounded to learn that he died during the Battle of Jutland on May 31st 1916 in the dark waters of the North Sea and not aboard the Titanic in 1912. A sea tragedy all the same but in a completely different context. He was a First Class Boiler Stoker, aged only 20 years, shoveling and stoking the large quantities of coal into the boilers to power the battle cruiser to which he was stationed; the HMS Indefatigable. He had been born on March 19th 1896 to Peter St. Ledger and Anne Delaney of Aghowle and the youngest of six children. Peter enlisted in the Royal Navy in Dublin and his personalised military number was SS-116654.

Imagine his fears and thoughts as he shoveled continuously into the flaming bellies of the large Babcock & Wilcox boilers, not knowing what was occurring up on deck. He would’ve felt each hit, possibly knocking him to the floor. He would’ve heard the screams of comrades. His eyes would’ve been teary with the heat, smoke and coal dust.

Unknown to Peter St. Ledger, the German battlecruiser, ‘Von Der Tann,’ was heavily blasting the ‘Indefatigable’ with twelve inch shells. It took one direct shot to the munitions hold to completely obliterate the ship within seconds. Peter St. Ledger would’ve most likely died instantly with the horrific explosion that would’ve occurred beside his boiler room. He and his fellow boiler crew would’ve been completely obliterated as the remains of the ship blasted two hundred feet into the air before disappearing beneath the murky waters. Of the crew of 1,019, only two survived.

And so I’ve told you the story of Peter St. Ledger; a mere young male from the townland of Aghowle, who would’ve played in the same fields as us as a child, visited Aghowle Church and shopped at Kenny’s grocer at the Crablane. It is sad that his memory was somewhat attached to another famous ship, the Titanic down through the years, thus highlighting that he was somewhat locally forgotten. Only his remaining cousins, the Byrne’s of Aghowle and the Suttons of Rath East have remembered Peter’s service in World War One.

As Peter and his comrades had no known grave, their names are inscribed at the Royal Naval Memorial at Hoe, Plymouth, England.